Lolita, light of my life, fire of my loins. My sin, my soul.

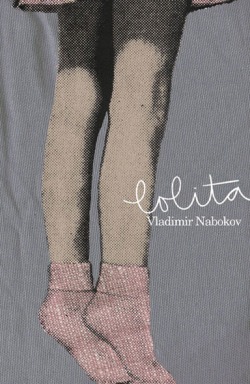

I’ve decided to totally approach a rather infamous and controversial novel for our first “serious” book and movie(s) review, Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov. This is the review of the novel and the first of a three part review, the second to reviews will be an overview of the two movies based on this novel.

Lolita, in my personal opinion is one of the most beautifully written novels of the twentieth century, but it is also one of the most misunderstood. When published in the 1950s, society criticized Lolita for its “frank sexuality”. Today, people look at it askance because of our increased sensitivity to child abuse and molestation. Unfortunately, conservative and liberal critics scrutinizing the surface story of Lolita, and panting maniacs real the novel while looking for titillating material, demonstrate and appalling ignorance of Vladimir Nabokov's "intentions".

If you've only heard of Lolita from its reputation as being "pornographic" material, you are in for a surprise when you read it. Yes, it does involve a lecherous, middle aged man chasing after a twelve year old "nymphet". Yes, the story plot is deeply disturbing but it is also a brilliant, funny, and witty. In short, Lolita is a literary rollercoaster which will delight you and dazzle you with the beauty of its language. Nabakov can make words jump through hoops you never even knew existed, while he explores the dark realms of obsession and longing through Humbert Humbert.

The narrator, Humbert Humbert, is a fascinating construction of a sympathetic villain. As readers, we find ourselves simultaneously repelled by his actions but still sympathetic to his yearning. We are utterly charmed by his wit, intelligence and verbal acrobatics, sometimes to the point where we lost sight of what he's doing to his object of desire, Lolita.

Humbert Humbert (a red-flag for readers is the Humbert’s name which signals that this story is going to take a lot of twists and turns) is a well-educated and sophisticated middle aged European gentleman of a cultured and privileged background. He has come to the United States, in New England as a professor of literature to teach in an elite private school. He is also a pedophile, who can only “love” adolescent girls. Humbert meets a woman who a daughter that he fancies. He marries her to get close to her twelve year old daughter, Dolores (his Lolita). He seduces the twelve-year old girl, and then goes on to have a year or so long "affair" with her.

I put the term "affair" in quotation marks, because it’s hard to describe a sexual relationship between a full grown male and a female child in such terms. Is it safe to say that most rational human-beings disapprove of such relationships? It is certainly safe to say that Nabakov knew when he wrote the novel that such a relationship is wrong. This is important. The tale is not only told in the context of a moral universe, but it is told by a character who knows that what he is doing is wrong but he is still compelled to commit his crime. Humbert may make a comment here and there about some medieval king marrying his twelve year old cousin, but in his heart he knows that he is a monster.

During the course of their year-long “relationship”, Humbert takes Lolita on a journey across, around, and through the United States, living in hotel rooms, and buying clothes and food on the move. Toward the end of this, we find one of the most moving paragraphs in literature:

And so we rolled East . . . We had been everywhere. We had really seen nothing. And I catch myself thinking today that our long journey had only defiled with a sinuous trail of slime the lovely, trustful, dreamy, enormous country that by then, in retrospect, was no more to us than a collection of dog-eared maps, ruined tour-books, old tires, and her sobs in the night--every night, every night--the moment I feigned sleep.

The Humbert’s revelation of such anguish on the part of his victim clearly works against the argument that this novel was merely intended to be pornographic material.

Humbert makes it clear that he loves his Lolita, in fact he almost worships her to a terrifying degree. He loves the way she moves. He loves the down on her arm. He loves her grace on the tennis court. He loves the way she flicks her head at him. He loves her toes and her shoes. He loves her name, especially the name he calls her-Lolita, not Dolores. He describes her in beautiful, poignant, poetic language, memorable and moving in every respect. Indeed the English language has rarely been used so wonderfully, but nowhere in this book does Humbert ever describe Lolita’s sexual characteristics, or comment in length or in glaring detail his physical relationship with Lolita.

Finally, there is no effort to shy away the effect of this sexual relationship has on Lolita. We learn through the novel that after she leaves Humbert, she enters into a series of tawdry sexual escapades at a very young an age with a debased playwright, Clare Quilty. We last see Lolita, in her late teens, married to a country-bumpkin and living in a clapboard shack surrounded by weeds.

Obviously, to anybody who has read the book, the presentation of the sexual subject matter is not objectionable. So what disturbs most people about Lolita? I think that with Lolita, Nabokov has perhaps unconsciously touched a social nerve. We want to believe that we, as humans are rational creatures. We want to believe that we know what is right, and we have set rules for ourselves to follow. Everybody agrees that murder is wrong. But sexual mores have changed and continue to change in our affluent Western societies. But Humbert Humbert who is the product of Western culture and life of privilege abandons all this in quest to satisfy his own desires. And through it all, he tries to use his training in Western logic and philosophy to justify what he is doing.

When you, as a reader, find yourself sympathizing with Humbert about Lolita's cruelties, try to remember that you are seeing everything through his eyes. Humbert has rationalized his behavior so deeply and reports it to the readers so beautifully, that we find ourselves accepting his interpretations of people and events at face value.

However, we must remember that Humbert is capable of the most monstrous of deceptions and of self deceptions. Read between the lines. Question his reading of events. Pay attention when his reporting is at odds with his interpretations of them. As one example, Humbert tells us that he was seduced by Lolita, giving us the impression that she was sexually mature and a willing partner. Contrast that with his throwaway mentioning of her performing for him in exchange for treats, and watching television as he took his pleasure in her. And don't ignore Lolita sobbing each night. (And also remember that Nabokov's original title for Lolita was Kingdom by the Sea after Edgar Allen Poe's poem, for any of you English/Literature college majors.) Nabokov has created a conundrum for his readers. He uses the most glorious tricks and delights of the English language to tell his tale of self-deception and rationalization masquerading as true love. The reader must look beyond the beautifully narrated prose to the grime beneath it, and appreciate the mastery that makes Lolita a beautiful and yet troubling masterpiece.

Some readers and critics view Lolita as a tragic love story while others consider it a celebration of the open road. Some even argue that Lolita is a metaphor for the clash between European and American culture. Lolita may well be all these things and more, but it is also a much darker chronicle of the Humbert’s mindset. Humbert's narrative is charming and full of old world conceit, but we must never forget that it is also a tool of disguise. Humbert self-consciously uses style to conceal the naked brutality of his craving and the harm it causes Lolita. He disguises himself as the doomed lover and portrays her as the tormenting muse.

We may read Lolita through the perspective of nymphet-obsessed Professor Humbert, but Nabokov himself described Humbert as a vain and cruel wretch who manages to appear 'touching’. Furthermore, anyone familiar with Nabokov's other works knows of his penchant for unreliable narrators, such as Charles Kinbote in Pale Fire. It's difficult to imagine Nabokov writing anything of poor quality. His prose has a natural flow and an effortless sophistication that I have never seen in any other writer of the English language. He writes with grace and maturity that lend his prose a certain amount of authority. Once can hardly question the master, and this may be why I was seduced by Lolita the first time I read it.

Nabokov portrays the erotic scenes and sensual images with a modesty based on artistic sensibility. Lolita is full of mythical and literary allusions; puns and anagrams that transcend linguistic boundaries; catalogues of quotidian life; parodies of Freudian psychology, popular culture, etc.; arcane and esoteric trivia; the melting pot of "high" and "low" culture; the bizarre coincidences that supplant the standard symbolism of most literature at that time; and so on. Humbert's comments on certain subjects and his sardonic asides are absolutely hysterical. And the final showdown between Humbert and perverted playwright Clare Quilty is a great study in dark humor.

During the first time I read Lolita, I was enchanted by the character of Humbert Humbert: his old world manner, his self-justifying narrative, and contempt for Freudian Psychology and Existentialism. However, the second time I read Lolita I had a far more troubling experience. I still enjoyed the novel's writing and characterization, but this time it struck me on a realistic level. I found myself empathizing with Lolita and imagining what the world must be like as she traveled around the country in the company of a foster parent who habitually molested her.

I was especially moved by the scene in which Humbert informs her that she cannot leave him because her mother is dead. Lolita runs out of the room but eventually returns to Humbert's bed and tearfully wraps her arms around him. When she does this, Humbert informs the reader that she simply had nowhere else to go to but to him. In that moment, I was suddenly immune to the charm of Humbert's narrative and enormously sad for Lolita. Nabokov has given us one of the greatest literary works of the century.

Review by Raine

RSS Feed

RSS Feed